Seattle Plastic Surgeon discusses the challenge of introducing new procedures to her practice.

This coming weekend thousands of Plastic Surgeons and their staff will decend on San Diego for the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. These meetings provide an opportunity to share ideas, techniques, new procedures, and new equipment and instruments.

Plastic surgeons tend to be very innovative and open to new ideas and it’s not unusual to come away from one of these meetings all fired up to try the latest and greatest.

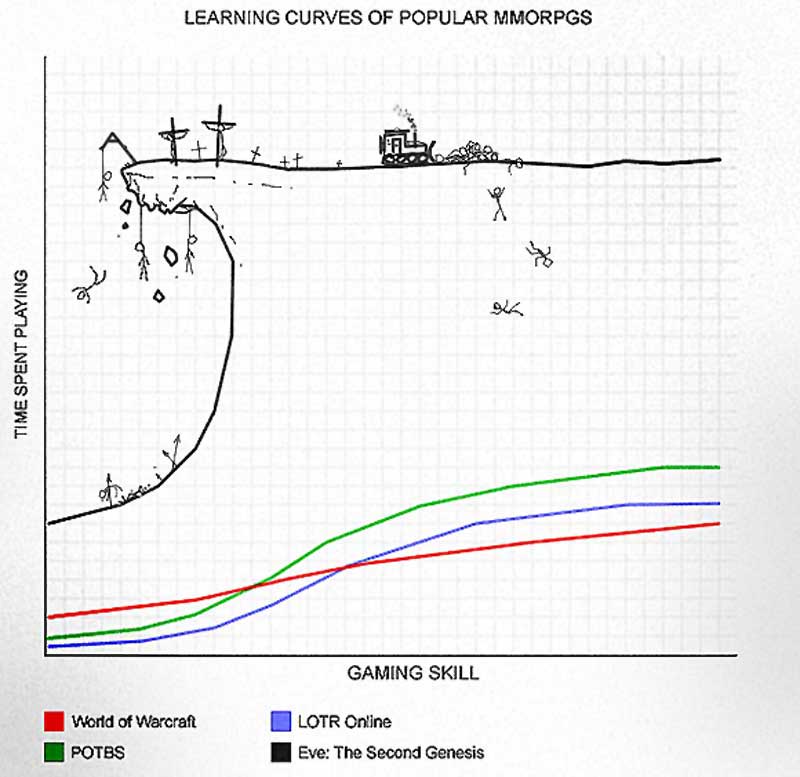

Enter the learning curve: With every new procedure or variation on a well established procedure, by definition someone has to be the first patient and that first patient may not get as good a result as the 10th or 100th or 1000th patient. Or maybe the surgeon, after a handful of cases, decides that this latest and greatest is not really an improvement and he/she abandons it altogether.

Sometimes the learning curve is very favorable and sometimes it is so harsh that I am not willing to even give it a try. An example of a favorable learning curve is transblepharoplasty browlift with Endotine fixation devices. The anatomy was familiar. The new instrumentation was eary to learn how to use. Risk to the patient was low. If it didn’t work, a conventional coronal brow lift could be done. After about half a dozen cases, I got very good at selecting patients with favorable anatomy for this procedure and now do this procedure frequently. Last year, after many, many patients, I had a failure of the fixation device on one side and had to redo that side. That single device failure has not dampened my enthusiasm.

A procedure that I just can’t bring my self to try is a deep plane a.k.a. subperiosteal face lift. This procedure was the latest rage 15 or 20 years ago. It was supposed to give the most natural looking and longest lasting facelift results. The downside is that the operative area is very close to where the facial nerves live. These are the nerves that control facial movement. A permanent injury to one of these nerves can be devestating. Also, postoperative swelling can take up to a year to resolve. There was a bit of a machismo aura attached to this procedure and maybe I just didn’t have large enough cajones to jump on this particular bandwagon. The benefit of this operation, IMO, did not justify the risk to the patient. And, these days, almost nobody talks about this procedure. The buzz just isn’t there.

When I embark on a new procedure, I am very honest with my patients about my expereince or lack thereof. I explain that it is a lot like cooking. If a cook has good basic skills, knowledge, and experience, making a new dish is not reinventing cooking, but rather applying those skills, knowlege and experience in a new way.

Thanks for reading! Dr. Lisa Lynn Sowder

@lisalynnsowder

@lisalynnsowder